| Iran

in the Age of the Raj

By David Meyler

August 2012

Iran in the latter half of the 18th century

lived under the shadow of Nader Shah (and

in some respects still does to this day).

He was born Nader Qoli on October 22, 1688,

a member of Turkic Afshar tribe. He rose to

become a beg — lord or chieftain —

of the Afshars, as well as one of the empire’s

most skilled generals under the reign of the

last of the Safavid shahs.

|

Nader Shah, by David Meyler.

|

In 1719, Mahmoud Ghilzai led an Afghan army

into Iran, and in 1722 deposed

the ruling Shah Sultan Husayn and had himself

made emperor. This was one of the lowest points

in the long history of Iran. His reign did

not last, however, and in 1725 Mahmoud was

assassinated by his own men, and a cousin,

Ashraf, was crowned, marrying a Safavid princess

in an attempt to give himself some legitimacy.

Nader Qoli Beg initially served with the

Afghans in a campaign against the Ozbegs,

but when Ashraf withheld his promised payment,

he joined a revolt in 1727 with 5,000 men,

in support of the Safavid heir, Tamasp II.

Nader defeated the Afghans and drove them

out of Khorasan. Ashraf attempted to flee,

after massacring 3,000 Persians in Isfahan,

but was hunted down and killed.

While Nader was busy in the east, Tamasp

II invaded Ottoman Turkey to build up a military

reputation for himself. By 1732, the shah

had managed to lose Armenia and Georgia to

the Turks. Nader was enraged and had the shah

deposed, and replaced by Tamasp’s infant

son, under the name Shah Abbas III. This clearly

showed who the real power was.

Immediately, Nader struck back at the Ottomans

and regained all the territory lost by Tamasp.

Abbas died, apparently of natural causes,

in 1736, and Nader, dropping all pretense,

had himself crowned shah.

In 1738, Nader Shah launched what is likely

his greatest military campaign. He invaded

Afghanistan through Kandahar and captured

Kabul and later Bukhara. Nader then hit Moghul

India, captured and sacked Delhi, and slaughtered

30,000 of its citizens. He returned to Iran

with much of the Moghul treasure horde, including

the famed Peacock Throne and the Koh-i Noor

diamond. Nader then, in 1743, resumed the

war against Turkey scoring more victories,

and picking up some territory at the expense

of the Russian Empire. He also built a fleet

in the Persian Gulf and conquered Oman.

Time of Troubles

Nader’s domestic policy was one of

increasing paranoia and cruelty. Tamasp II

and his two surviving sons were murdered in

1740. Nader had his own son blinded and executed

many Persian nobles out of largely imaginary

fears of insurrection. He also made a failed

attempt to make Sunni Islam the state religion,

alienating many of his Shia supporters. Finally,

in 1747, while on campaign in Kurdistan, a

group of his own officers attempted to assassinate

him at dawn. “Better we make breakfast

of him before he makes supper of us,”

was their credo. The 61-year-old shah, while

caught by surprise, managed to kill two of

his attackers before he was overcome and killed.

Sometimes called the Second Alexander, the

Napoleon of Iran or the last of the great

Asian conquerors, Nader had expanded Iran’s

boundaries to their greatest extent since

the Sassanids in early medieval times. But

it was not to last. Succeeded by Adil Shah,

his nephew, the new emperor promptly had all

of Nader’s sons and grandsons executed,

save one, the 14-year-old Rukh. Adil was soon

deposed by his brother, who was them deposed

and murdered by his own troops. Adil was also

eliminated at this time. Rukh was then made

shah, deposed and blinded, then reinstated,

deposed and reinstated once again.

In short, the empire fell into anarchy, with

each of the various provincial governors ruling

their own petty kingdoms. Only in the south

was the warlord Karim Khan, 1753-1779, able

to maintain a core territory, what is historically

termed the Zand dynasty.

Qajar Revival

Upon the death of Karim, Agha Mohammad Khan,

a leader of the Turkic Qajar tribe from Azerbaijan,

began an attempt to reunite the empire. At

the age of six Mohammad had been castrated

on the orders of Adil Shah to prevent him

from becoming a political rival – it

didn’t work and it did not prevent Mohammad

Khan from establishing a dynasty. He had been

held captive for 16 years in Shiraz but managed

to finally escape in 1779.

In a long series of campaigns, Mohammad Khan

overcame all his rivals. The last of Zand

dynasty, Lotf’Ali Khan, was defeated

in 1794. He established the new capital at

Tehran, then a small provincial town of 15,000.

In 1796 Agha Mohammad led a successful expedition

against the Christian Kingdom of Georgia,

which was then reincorporated into Iran (raising

Russian ire). He conquered Khorasan, the last

centre of resistance to his authority; there

the ruler Shah Rukh (the blind, non-dancing grandson of

Nader Shah) was tortured to death. Mohammad

Khan was formally crowned shah in 1796, but

he did not long enjoy his hard won victory.

The following year, he was assassinated and

was succeeded by his nephew Fath Ali Shah.

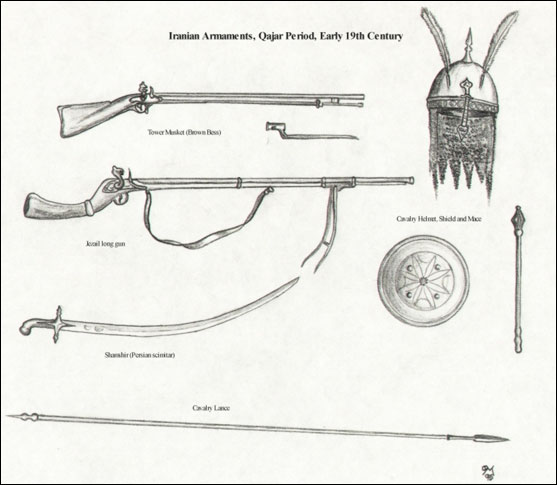

Iranian weapons by David Meyler.

War with Russia

Fath Ali ruled to 1834 and finally reestablished

a degree of stability. With the aid of the

able Mirza Assadolah Khan, Minister of War

and the Crown Prince Abbas (or Abbas Mirza,

mirza means prince – that’s the

leader counter Abbas M. in Soldier Emperor),

a new army based on the Napoleonic model was

created. Pressure from Russia advancing into

the Caucasus led to the first Russo-Persian

War (1806-1813). The Russian forces generally

prevailed thanks to superior artillery. Still,

Abbas Mirza, using the terrain and superior

tactics, managed to win a number of victories

to stave off total defeat. The Treaty of Golestan,

however, confirmed the earlier Russian annexation

of the kingdom of Georgia, as well seeing

the loss of parts of the northern Caucasus.

The nation began to open itself up more to

European influence, and while Abbas Mirza

sent Iranians abroad to study European technology,

British advisors were brought into the country

to further reform the army (followed by the

French and Austrians in later decades). The

Ottomans were stunned by the performance of

the new Iranian army at the battle of Ezeroum

in 1821, which confirmed the existing boundaries

between the two empires.

Fath Ali Shah, however, then overstepped

himself, leading to the second Russo-Persian

War 1826-28. While the Iranian army under

Abbas Mirza had proved itself a dominant regional

force, it was still no match for a major power

like Russia, which was able to field a much

larger and better-equipped army. At the Treaty

of Turkomanchai, Iran ceded much of its northern

territories, the entire area north of the

Aras River (comprising present-day Armenia

and the Republic of Azerbaijan), and had to

pay Moscow a huge war indemnity.

The Great Game

Fath Ali died in 1834 and was succeeded by

his grandson Mohammad Shah. He attempted twice

without success to recapture Herat, an ancient

province of the Iranian empire, but long since

part of Afghanistan. Here, Iran was dangerously

getting drawn into the “Great Game.”

Mohammad Shah was pro-Russian, and while the

Afghan forces on their own were no match for

the Iranian army, the Afghans had British

backing (at least, while fighting the Persians).

Mohammad Shah died in 1848, with his son

Naser-ed-Din, taking the throne. He ruled

for most of the remainder of the century.

Iranian designs on Herat did not end, leading

to an all-out war with British India in 1856-57.

There was one battle of note, the Battle of

Khosab on February 8, 1856. The British won

a clear tactical victory using a large square

formation to beat off the Iranian cavalry.

But the fighting was not as one-sided as one

is led to believe from British sources, and

while the British had better firearms and

artillery, there were gross administrative

and supply deficiencies (as was also seen

in the Crimean War) that forced a British

retreat.

Still, the defeats against Russia and Britain

proved demoralizing, and Iran, while undergoing

something of a cultural revival under Qajar

rule, increasingly fell under the sphere of

influence of its two powerful neighbours.

In the political chaos following the assassination

of the aging shah in 1896, Iran became a virtual

colony of the Europeans, divided into a Russian

and a British sphere of interest. It would

not be until the 1920s, following the double

cataclysms of the First World War and Russian

Revolutions, before the country again gained

a measure of independence.

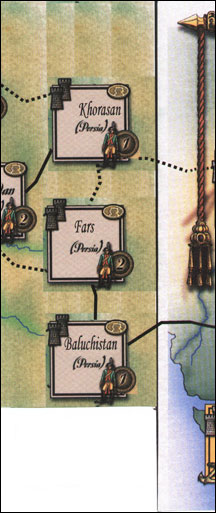

Variant: East Meets West

Soldier Raj and Soldier Emperor

already have provisions for linking their

maps. This variant adds an overland option

when playing linked scenarios.

The

area missing between the two maps was not

great, so I made a small map overlay to add

eastern Persia. While not entirely to scale,

it serves as a link between the two maps.

The rules for inter-map movement remain unchanged,

but units can also now move overland (this

opens another option to intervene in Central

Asia, especially for Russia). The

area missing between the two maps was not

great, so I made a small map overlay to add

eastern Persia. While not entirely to scale,

it serves as a link between the two maps.

The rules for inter-map movement remain unchanged,

but units can also now move overland (this

opens another option to intervene in Central

Asia, especially for Russia).

Three new Persian land areas are added to

the Soldier Emperor map:

Khorasan (Fortifications 2, Money

1, Manpower 1), with a mountain route connecting

to Baku, a land route to Azerbaijan and mountain

route to Fars. Khorasan also connects to the

Soldier Raj map with a mountain route to Afghanistan.

Fars (Fortification 2, Money 1, Manpower

2), with a mountain connection to Azerbaijan,

a mountain connection to Khorasan and a land

route to Baluchistan.

Baluchistan (Fortification 2, Money

1, Manpower 1), with a land route to Fars.

Bauchistan also connects to the Soldier

Raj map with a land route to Baroda.

The map overlay joins the southeast portion

of the Soldier Emperor map with the

northwest frontier of Soldier Raj.

Persian forces remain unchanged.

Click here to

download the map!

Click

here to order Soldier Emperor! |