Atlantic Breakout

Battle Cruiser Raid Proposals

by Mike Bennighof, Ph.D.

May 2025

In the summer of 1915, Captain Max Hahn of the battle cruiser von der Tann wrote a proposal in the ship’s war diary, calling for a raid into the North Atlantic by his ship. His boss, Scouting Forces commander Vice Admiral Franz Hipper, shot it down in a withering written rebuke. German doctrine was clear; the battle cruisers served with the High Seas Fleet and not on independent long-range operations. In the summer of 1915, Captain Max Hahn of the battle cruiser von der Tann wrote a proposal in the ship’s war diary, calling for a raid into the North Atlantic by his ship. His boss, Scouting Forces commander Vice Admiral Franz Hipper, shot it down in a withering written rebuke. German doctrine was clear; the battle cruisers served with the High Seas Fleet and not on independent long-range operations.

By the following summer, in the wake of the Battle of Jutland (and Alfred von Tirpitz’s forced retirement), Hipper sang a very different tune. He now proposed not only raids by individual battle cruisers, suggesting Moltke or Derfflinger, but even an operation by four of them at once. This would greatly disrupt commerce, draw away British forces from the North Sea, and give the Germans the chance to overwhelm out-gunned British armored cruiser squadrons.

The formal proposal came in late 1916 or early 1917, with the staff work overseen by Hipper’s chief of staff, Commander Erich Raeder (who would command the German Kriegsmarine in the next war, and direct similar operations with more suitable ships). The battle cruisers would steam into the Atlantic, either by dashing through the English Channel or taking the long route around the northern tip of Scotland. Colliers would slip past the British blockade in advance of the battle cruisers, to meet up with the warships at pre-arranged rendezvous. The raiding squadron would also look to make use of neutral American ports, with the German supply service making sure that coal would be available before the 24-hour limit recognized under international law began, allowing the Germans ships to take on as much fuel as possible.

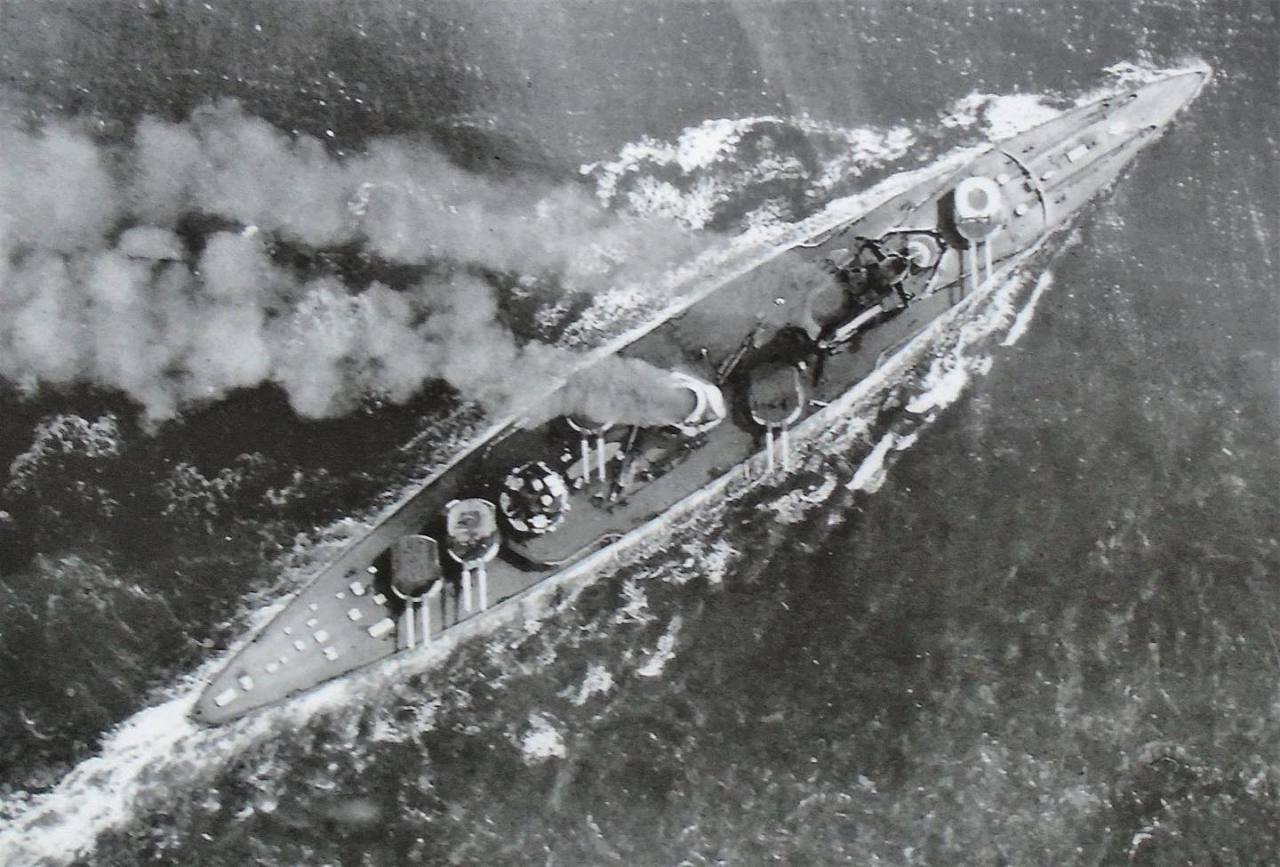

SMS Derfflinger, the Iron Dog.

Operationally, the raiding squadron would have two prime targets: merchant ships crossing the Atlantic, and the British cruiser squadrons stationed in North America and the Caribbean to offer them rather distant protection. The British had not yet instituted a convoy system, which would have left the ships bearing food and fuel to feed Britain’s population (and her war industry) absolutely vulnerable to any German warship they encountered. That reality also made the deployment of battle cruisers a case of massive overkill.

Britain had two cruiser squadrons operating in the area at the time. The 4th Cruiser Squadron, headquartered in Bermuda, had six armored cruisers and an even older protected cruiser. The 9th Cruiser Squadron, based in Freetown, Sierra Leone, but often deployed in the North Atlantic and Caribbean, had four more armored cruisers and five armed merchant cruisers, all of the latter converted from large passenger liners. Hipper’s four battle cruisers could have run down and obliterated either of these squadrons with little trouble. But what point would that serve?

In strategic terms, the proposal looked to widen the battlefield well outside the North Sea. The German command celebrated what they termed a victory in the Battle of Jutland (what they called the Battle of the Skagerrak), but Hipper instantly saw the implications. The High Seas Fleet had been lucky to escape intact, and could not match the British Grand Fleet in open battle. By destroying the far-flung British cruiser squadrons, Hipper hoped to force the British Admiralty to detach modern, heavy ships from the Grand Fleet to replace them.

In practical terms, the German battle cruisers had demonstrated the necessary range during pre-war exercises. Von der Tann visited South American ports in early 1911, and Moltke went to the United States a year later. Both trips went well; the next German battle cruiser, Goeben, went to the Mediterranean in 1913 instead of making a long-range cruise. For the summer cruise of 1914, the High Seas Fleet planned to send Seydlitz and, if she could be made ready in time, Derfflinger to represent Germany at the opening of the Panama Canal.

That heavy smoke from SMS Seydlitz speaks to poor-quality coal.

Those deployments took place during peacetime, under optimal conditions. A wartime operational tempo had shown what many technical experts within the German Navy had already suspected: naval technology, particularly turbines, had outrun the materials and techniques available to translate those concepts into working machinery. All of the German battle cruisers suffered breakdowns from the heavy use of their turbines: blades shearing off, casings cracking, bearings overheating. That included the propellor shafts they drove; Moltke had repeated difficulties with the turbines cranking out more power than could be translated into shaft rotation.

Poor coal contributed to those problems, as excessive ash and smoke fouled the boilers and the need to shovel vast amounts of low-grade fuel to keep the fires burning hot wore out the stokers and trimmers. A load of poor coal meant that the ship could not make its top speed, and burned excessive amounts. All of the battle cruisers received auxiliary oil sprays to help with this problem, but ever dousing the coal with petroleum could not make it the equal of the hard, high-density fuel for which the ships’ machinery had been designed.

And then there was the back-breaking work of refueling a coal-burning ship. A generation later, warships could be topped off by connecting a hose to their tanks, but during the Great War, coal had to be moved by hand, with dust-covered sailors wielding shovels and wheelbarrows. Raeder and his staff acknowledged the difficulty of coaling such huge and hungry ships in isolated fjords along the coasts of Greenland or Iceland, even if a rendezvous could be made successfully.

In all likelihood, if four battle cruisers steamed out of Wilhelmshaven on a North Atlantic raid, not all of them would return. A distinct possibility loomed that all four of them could be lost without even encountering the enemy.

The Iron Dog fires a broadside.

The balance of high risk against low reward drew the opposition of both Admiralty chief of staff Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff and Kaiser Wilhelm II himself. Unrestricted submarine warfare resumed in February 1917, initially proving extremely successful. It also brought the United States into the war, thereby depriving potential German raiders of neutral ports in which to refuel, and adding a huge additional fleet to the Allied side (which would also provide battleship escorts for the convoys carrying American troops to Europe).

Wilhelm II remained skeptical of using heavy ships as commerce raiders, approving a more conservative raid in 17 but only if the commander of the High Seas Fleet could abort it at any time. That in essence restricted operations to the North Sea, and the High Seas Fleet did try to act against convoy traffic in both the northern and southern reaches of the North Sea basin. But that was not the same as the proposals by Hahn and Hipper for a daring and likely foolish deep raid west of Brtain.

Atlantic Breakout 1915 is a Campaign Study based on these proposals, using pieces from Great War at Sea: Jutland 2e on the map from Second World War at Sea: Bismarck. Jutland’s map doesn’t cover enough of the Atlantic to show the breadth of the proposed operations. On the Bismarck map, you can see the vastness of the gray ocean. There’s plenty of room to hide, for both the hunter and the hunted.

Superficially, the scenarios look a great deal like those of Bismarck, with the redoubtable Iron Dog in the role of heavy raider. But coal-fired ships have an insatiable hunger for fuel, and they can’t feed it easily. Underway replenishment is not an option, and there’s very little shelter in the North Atlantic. That makes for exactly the sort of question I like to answer in a Campaign Study: the proposal looked good on paper. And now we can play it out in a wargame.

You can order Atlantic Breakout right here.

Sign up for our newsletter right here. Your info will never be sold or transferred; we'll just use it to update you on new games and new offers.

Mike Bennighof is president of Avalanche Press and holds a doctorate in history from Emory University. A Fulbright Scholar and NASA Journalist in Space finalist, he has published a great many books, games and articles on historical subjects; people are saying that some of them are actually good.

He lives in Birmingham, Alabama with his wife and three children. He misses his lizard-hunting Iron Dog, Leopold.

Daily Content includes no AI-generated content or third-party ads. We work hard to keep it that way, and that’s a lot of work. You can help us keep things that way with your gift through this link right here.

|