| Saipan 1944:

Scenario Preview, Part Seven

By Mike Bennighof, Ph.D.

April 2025

There’s an inherent problem in many military history wargames: one side wins, and the other loses. The problem lies in how they win and lose. At the strategic (where nations fight) and operational (where armies fight) scales, it’s rare for the contest to end in a nail-biting finale. No general or political leader wants a fair fight. They don’t want to fight unless they’re quite sure they will win. There’s an inherent problem in many military history wargames: one side wins, and the other loses. The problem lies in how they win and lose. At the strategic (where nations fight) and operational (where armies fight) scales, it’s rare for the contest to end in a nail-biting finale. No general or political leader wants a fair fight. They don’t want to fight unless they’re quite sure they will win.

For a hopeless situation, like the final days of the Japanese stand on Saipan in the summer of 1944, that doesn’t make things very interesting at the higher levels. But at the tactical level, where the Panzer Grenadier series lives (platoons and batteries), even a badly defeated enemy can turn and inflict a defeat on their seemingly victorious foes.

The Japanese knew the battle to be lost, down to the private soldiers in their “octopus holes” (caves with many entrances). But they knew they could still inflict defeats on the Americans in front of them. And so they kept trying, in the spirit of ganbaru.

Chapter Seven

Streets of Garapan

Once the Americans seized the high ground in the center of Saipan, Japanese defenses finally began to crumble. Despite inflicting heavy losses on the Americans, their own casualties had been much higher, and the streams of civilian refugees headed northward including large numbers of unarmed, unorganized soldiers and sailors. The remaining field hospitals had no medicines, and could only offer the severely wounded a hand grenade to end their suffering.

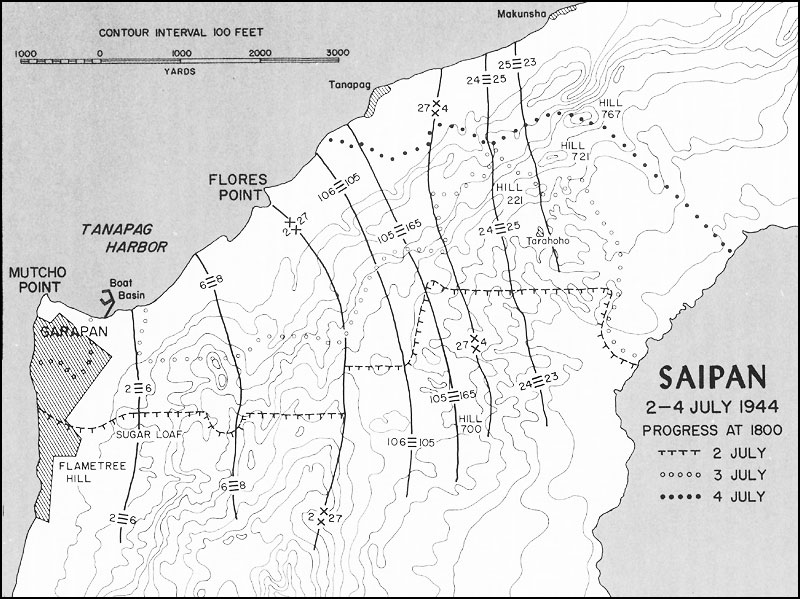

Open in new tab to embiggen this map.

But in the field, Japanese troops continued to resist, with the Army troops trying to form a new line though their higher-level commanders had lost touch with their troops and most senior field-grade officers had been killed. Naval ground troops continued to hold the island’s capital, Garapan, and disordered Army units joined them there.

The Japanese 31st Army put together a line, but many units had been isolated or almost wiped out. About 100 artillerymen went to the front as infantry, having lost all of their guns. Lt. Col. Hideo Okawa, chief of the 43td Infantry Division Accounting Department, led most of the divisional support staff, about 300 survivors, forward to fight as well. Lt. Col. Tadashi Goto’s 9th Tank Regiment had begun the battle with 48 tanks and 990 men; Goto himself was dead, and only about 100 men and three damaged Type 95 light tanks remained.

All three American divisions had become worn down, and corps commander Holland M. Smith hoped to pull one of his Marine divisions out of the line to refit for the pending invasion of Tinian, the island just to the south-west of Saipan. The three American divisions would pivot leftward, and once Saipan’s capital, Garapan, had been taken the 2nd Marine Division would be out of the fight. The plan looked good on paper.

Scenario Thirty-Four

Flametree Hill

29 June 1944

Flametree Hill stood directly in the path of the 2nd Marine Regiment, driving up Saipan’s western shore toward the capital of Garapan. A small Japanese force had dug itself into the hill’s many caves, under the camouflage of the many orange-red flame trees covering the slopes. From there, they rained down automatic weapons fire on Marines trying to edge past and enter the town, then race back into their caves before Marine artillery could catch them in the open. Yet the hill would have to be secured before Garapan could be attacked. Flametree Hill stood directly in the path of the 2nd Marine Regiment, driving up Saipan’s western shore toward the capital of Garapan. A small Japanese force had dug itself into the hill’s many caves, under the camouflage of the many orange-red flame trees covering the slopes. From there, they rained down automatic weapons fire on Marines trying to edge past and enter the town, then race back into their caves before Marine artillery could catch them in the open. Yet the hill would have to be secured before Garapan could be attacked.

Conclusion

Saipan marked the first use of the VT fuze in ground combat. The Japanese came out of their caves, only to find a devastating barrage of shells that exploded just above the ground (thanks to that proximity fuze). The Marines drove off or killed the handful of dazed survivors, opening their path to Garapan.

Notes

The Japanese have another tough hilltop position to defend, but this time the Marines have proximity fuzes for their artillery. The Japanese player knows this, where his or her historical counterpart did not, but it’s still going to be tough to hold out against that sort of firepower.

Scenario Thirty-Five

East of Garapan

2 July 1944

As the 6th Marines pushed forward through rugged ground slightly to the east of Garapan, the regiment’s 3rd Battalion encountered strong resistance from Japanese troops dug in along a ravine. They told their regimental commander, Colonel James P. Riseley, that the Japanese had three field pieces with them. Riseley ordered his men to bypass the obstacle, leaving the 3rd Battalion’s Company B to deal with the Japanese holdouts. As the 6th Marines pushed forward through rugged ground slightly to the east of Garapan, the regiment’s 3rd Battalion encountered strong resistance from Japanese troops dug in along a ravine. They told their regimental commander, Colonel James P. Riseley, that the Japanese had three field pieces with them. Riseley ordered his men to bypass the obstacle, leaving the 3rd Battalion’s Company B to deal with the Japanese holdouts.

Conclusion

The Japanese had lost all their artillery by this point in the battle; the weapons reported by the Marines were likely battalion support guns. These gave the Japanese little advantage in the dense terrain, where the Marines reduced the Japanese strongpoints one by one, often after short-range exchanges of thrown hand grenades.

Notes

Marine infantry advances against Japanese artillery. That firepower isn’t going to help the Japanese all that much, so they need to inflict as many quick casualties as they can since the Americans are very loss-averse in this scenario.

Scenario Thirty-Six

Tokyo of the South Seas

2 July 1944

The Americans had initially spared Garapan from heavy bombardment, hoping to use the town as a base for later operations. American planes even dropped flowers to the civilian population to assure them of American good will. But when Japanese naval troops showed their determination to hold the town, planes, ships, and artillery all blasted what had been known as the “Tokyo of the South Seas,” flattening most buildings and damaging all of the rest except for Garapan’s two red-painted whorehouses. Then the Marines advanced, supported by tanks. The Americans had initially spared Garapan from heavy bombardment, hoping to use the town as a base for later operations. American planes even dropped flowers to the civilian population to assure them of American good will. But when Japanese naval troops showed their determination to hold the town, planes, ships, and artillery all blasted what had been known as the “Tokyo of the South Seas,” flattening most buildings and damaging all of the rest except for Garapan’s two red-painted whorehouses. Then the Marines advanced, supported by tanks.

Conclusion

The Japanese fought in the ruins of Garapan for most of the day, losing three-quarters of their strength in the process: when the Marines encountered a Japanese-held building (or the ruin of one), they obliterated it with tank and artillery fire, flamethrowers, and explosive charges. That evening the naval troops withdrew, leaving behind a platoon of South Seas Military Police led by Lt. Magoshige Koike, who had been guarding the joint Army-Navy headquarters building in Garapan. Koike apparently refused orders to retreat and urged his men to “die while killing at least one American soldier.” All but one died without killing anyone, with the final man retreating to join another MP unit.

Notes

You get it all in Saipan 1944, including a city fight. The Japanese are well-fortified with a good bit of support weaponry plus some armed casemates. The Marines fling it all at them: tanks, flamethrowers, tanks with flamethrowers and engineers. This one is going to be a tough fight.

And that’s Chapter Seven. Next time, it’s Chapter Eight (the end!).

Click here to order Saipan 1944 right now.

Please allow an extra four weeks for delivery.

Pacific Islands Package

Saipan 1944 (Playbook edition) Saipan 1944 (Playbook edition)

Marianas 1944

Leyte 1944

Retail Price: $156.97

Package Price: $125

Gold Club Price: $100

You can order the Pacific Package right here.

Please allow an extra four weeks for delivery.

Sign up for our newsletter right here. Your info will never be sold or transferred; we'll just use it to update you on new games and new offers.

Mike Bennighof is president of Avalanche Press and holds a doctorate in history from Emory University. A Fulbright Scholar and NASA Journalist in Space finalist, he has published a great many books, games and articles on historical subjects; people are saying that some of them are actually good.

He lives in Birmingham, Alabama with his wife and three children. He misses his lizard-hunting Iron Dog, Leopold.

Daily Content includes no AI-generated content or third-party ads. We work hard to keep it that way, and that’s a lot of work. You can help us keep things that way with your gift through this link right here.

|