| Jutland:

1915: The Idle Year, Part One

By Mike Bennighof, Ph.D.

November 2021

The German defeat at the Battle of Dogger Bank cost High Seas Fleet commander Friedrich von Ingenohl his job. Most of the fleet’s senior officers had wanted a more aggressive stance for some time, agitating for the appointment of Reinhard Scheer, then the commander of Third Battle Squadron. Instead, Kaiser Wilhelm II tapped Hugo von Pohl, Chief of the Admiralty Staff and a vocal advocate of unrestricted submarine warfare against British merchant shipping and neutral shipping trading with the British Isles. The German defeat at the Battle of Dogger Bank cost High Seas Fleet commander Friedrich von Ingenohl his job. Most of the fleet’s senior officers had wanted a more aggressive stance for some time, agitating for the appointment of Reinhard Scheer, then the commander of Third Battle Squadron. Instead, Kaiser Wilhelm II tapped Hugo von Pohl, Chief of the Admiralty Staff and a vocal advocate of unrestricted submarine warfare against British merchant shipping and neutral shipping trading with the British Isles.

“A more unlikely choice could not have been made,” Scouting Forces commander Franz Hipper observed. Alfred von Tirpitz, the Navy’s state secretary, said the news “was received with the greatest astonishment.”

Pohl took command on 2 February 1915, and two days later issued orders to commence unrestricted submarine warfare. Tirpitz had thrown the possibility into public view in November 1914, in an interview with an American newspaper that soon enough appeared in Germany. Senior German naval leaders had only just begun to consider such a step, with Pohl strongly in favor. The British had ignored the 1909 London Declaration Concerning the Laws of Naval War, which held that non-military cargo – including food – could not be stopped by a naval blockade. When the German government instituted food rationing in January 1915, citing what it called the illegal British blockade, the German public recalled Tirpitz’s interview and pressured the government to use submarines to retaliate.

Pohl’s hasty declaration took even many of his admirals by surprise. The German Navy had just 36 submarines in service at the time, only 15 of them capable of extended cruises in enemy waters. The boats had been designed, their crews had trained and their commanders had developed doctrine to attack enemy warships. An entire methodology of commerce warfare would have to be developed on the fly.

This first effort at unrestricted submarine warfare did not go well. The boats sank just under 800,000 tons of shipping in seven months, against the loss of 15 submarines. Though tragic for the sailors involved, the sinkings had little impact on Britain’s overseas trade: Britain had 21 million tons of shipping available, and not all of the losses had been British. The cost in international standing (and in submarines) did not justify the results.

Historians on the whole have not been kind to Pohl, accusing him of timidity or worse, and often claiming that the High Seas Fleet did not sortie under his command. The first charge has some validity, while the second is blatantly false. Pohl’s timidity echoed that of the Supreme War Lord: Kaiser Wilhelm II had been shocked by the loss of the big armored cruiser Blücher at Dogger Bank, and would not countenance further risk of the heavy ships. In Pohl, Wilhelm found someone unlikely to challenge this attitude.

The High Seas Fleet undertook operations in the North Sea throughout the year, though not proceeding as far from its bases as it had previously. The British Grand Fleet, likewise, also entered the North Sea throughout 1915. Radio intercepts tipped off the British when the Germans went to sea, but the Grand Fleet did not proceed as far south as it had previously. But both fleets were at sea more than once, and Pohl could easily have been embroiled in a fleet battle with Jellicoe on several occasions.

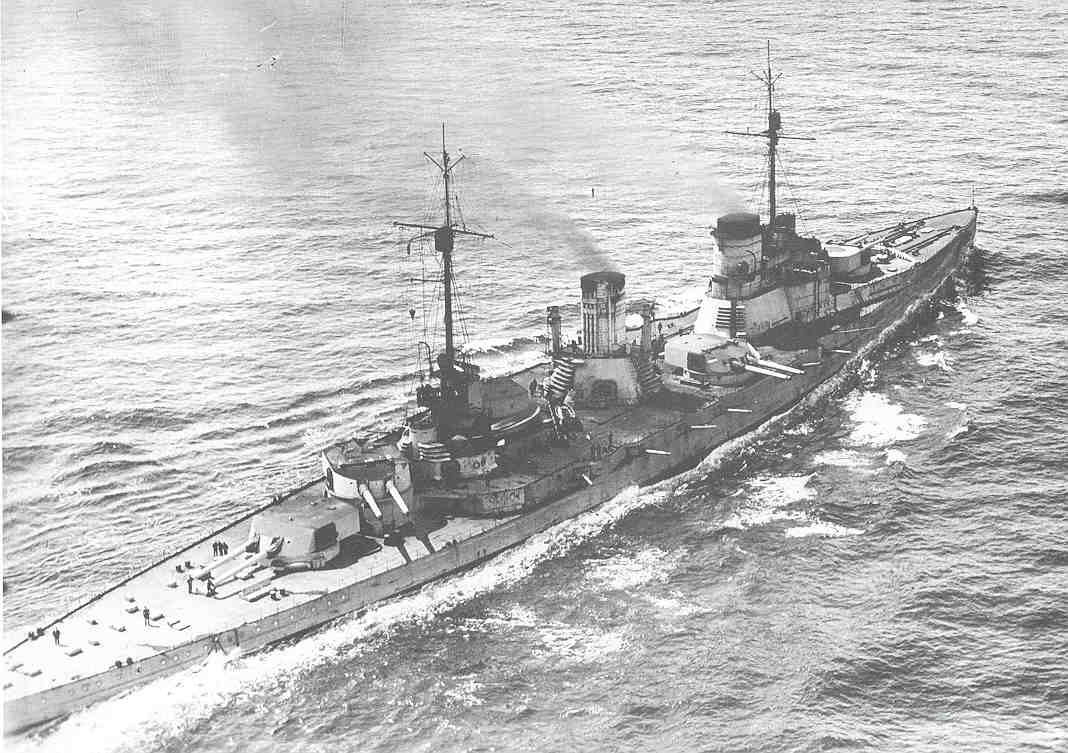

Battle cruiser Seydlitz in undamaged condition. A rare photo indeed.

During the first weeks of Pohl’s command, the vital battle cruisers of First Scouting Group were not fully available. Von der Tann missed the Battle of Dogger Bank due to maintenance work, which she completed on 3 February, followed by three more days in late February. Moltke was not hit by British fire during the battle, but fired 276 280mm shells and needed some work on her heavy guns including replacement of one gun barrel, which took place in the middle of the month. Seydlitz suffered severe damage; dockyard repairs lasted until 1 April, followed by several weeks of weapons calibration and training. Derfflinger received just one 13.5-inch shell hit, and was under repair until 17 February.

The battle cruiser commanders, and Hipper, had all complained of the low-quality coal they had shipped before the Dogger Bank operation, limiting their speed. Derfflinger’s skipper, Ludwig von Reuter, pointed out that his new ship had clean boilers and should have made 27 knots, but struggled to reach 24 knots. To help remedy that, during February and March the battle cruisers received oil sprayers to increase temperatures in their coal-fired boilers.

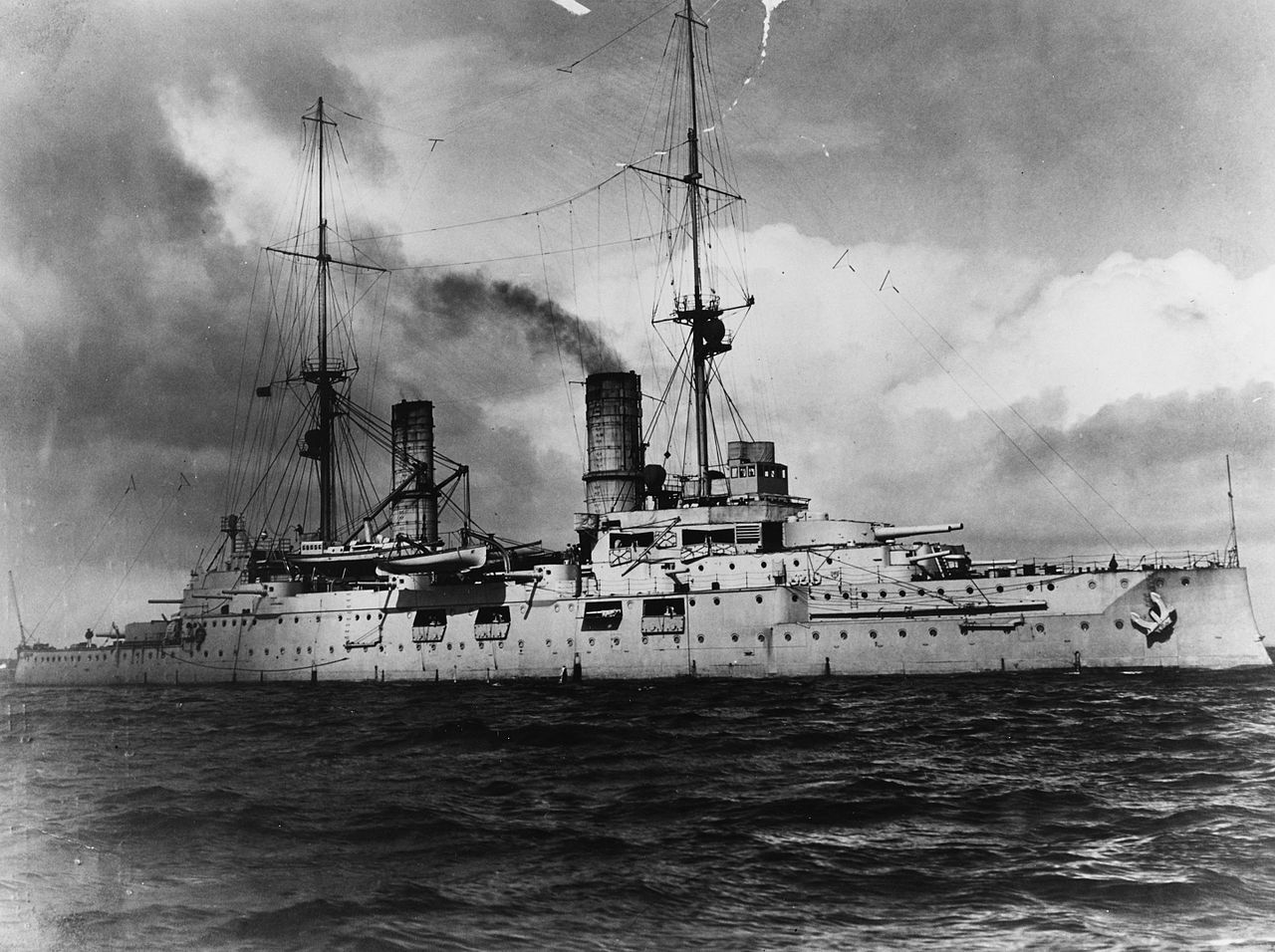

In a long-overdue move, Pohl also used his current credibility with the Kaiser to retire the ancient coast defense ships and pre-dreadnought battleships of the V and VI Battle Squadrons. They had actually accompanied the High Seas Fleet on several sorties during the first months of the war, and thankfully none had been lost – they lacked the armor to protect themselves from enemy shells, the guns to strike back, or the speed to escape even the weakest British battleship. Their maximum armament consisted of three 240mm (9.4-inch) guns for the Siegfried-class coast-defense ships; the Kaiser-class pre-dreadnoughts boasted four of them. The coast defense ships could make 15 knots when new while the Kaisers had touched 17 knots, but none of them could make even that anymore.

That move freed up several thousand officers and seamen; not all of the crews could be re-assigned, as the ships continued to exist as harbor watch vessels, floating barracks and offices, and one of the pre-dreadnoughts became a training ship. Pohl made another radical move that held out the possibility of increasing the High Seas Fleet’s fighting power, retaining one of the withdrawn pre-dreadnoughts as a “headquarters ship” and only boarding the fleet flagship Friedrich der Grosse for active operations at sea. That kept one of the fleet’s best fighting units from becoming a “floating hotel” as had been the case under Ingenohl and happened in many other navies.

The worthless pre-dreadnought Kaiser Wilhelm II became a headquarters ship.

Within days, German naval intelligence received disturbing news from the naval attaché to the United States. Commander Karl Boy-Ed, passed along rumors that the British planned a landing in March 1915 along the North Sea coast of Schleswig-Holstein. They would employ several of the new divisions of the “Kitchener Army,” and Denmark would enter the war on the Allied side after their beachheads had been secured. The ultimate goal would be to secure the North Sea outlet of the Kiel Canal and then drive on the High Seas Fleet’s North German bases.

Boy-Ed, the polyglot, cosmopolitan son of a Turkish businessman and a German novelist, had been the chief of naval intelligence before the war and was considered to have both excellent sources among the Americans and a well-honed instinct for trustworthy information. This tip could not be ignored, and the High Seas Fleet spent most of March on alert while torpedo boats and light cruisers swept the Helgoland Bight for any sign of an invading British fleet.

On the other side of the North Sea, the British had been mostly idle. The battle cruiser Lion required lengthy repairs after Dogger Bank. Tiger had also been damaged while Indomitable suffered an unrelated electrical fire. Sir John Jellicoe, the Grand Fleet commander, too the opportunity to rotate his squadrons between the wind-swept, barren anchorage at Scapa Flow and Invergordon in Cromarty Firth, where the ships could receive minor refits and the crews could enjoy some shore leave.

Boy-Ed’s warning was not completely off-base: the British were preparing an invasion, but not in Schleswig-Holstein. Additional intelligence revealed that many of the Channel Fleet’s pre-dreadnoughts and the new super-dreadnought Queen Elizabeth had gone to the Aegean Sea to support the invasion of Gallipoli at the entrance to the Turkish Straits.

With that information in hand, the High Seas Fleet could undertake an offensive mission.

Click here to order Jutland right now.

You can order Jutland: Dogger Bank right here.

Sign up for our newsletter right here. Your info will never be sold or transferred; we'll just use it to update you on new games and new offers.

Mike Bennighof is president of Avalanche Press and holds a doctorate in history from Emory University. A Fulbright Scholar and NASA Journalist in Space finalist, he has published more books, games and articles on historical subjects than anyone should.

He lives in Birmingham, Alabama with his wife, three children, and his Iron Dog, Leopold.

Want to keep Daily Content free of third-party ads? You can send us some love (and cash) through this link right here.

|