An Army at Dawn:

The Tunisian Campaign, An Overview

by Mike Bennighof, Ph.D.

March 2022

American and British troops landed in French North Africa on 8 November 1942, coming ashore at Casablanca in Morocco and at Oran and Algiers in Algeria. The invasion did not include Tunisia, as the waters offshore were considered too easily dominated by Axis aircraft based in Sicily. American and British troops landed in French North Africa on 8 November 1942, coming ashore at Casablanca in Morocco and at Oran and Algiers in Algeria. The invasion did not include Tunisia, as the waters offshore were considered too easily dominated by Axis aircraft based in Sicily.

The campaign in Tunisia began slowly, with the British 78th Division, supported by American armored detachments, advancing into the French protectorate out of Algeria beginning on the 16th. That pause gave the Axis the chance to pour reinforcements into Tunisia, until then under a French regime loyal to the puppet Vichy government. The Axis forces included small elite units (German paratroopers and Italian marines) and good regular units (the German 10th Panzer Division and Italian 1st “Superga” Infantry and 131st “Centauro” Armored divisions), but most of the troops were hastily organized from replacement depots and training centers.

The British skirmished with a German probe on the next day, but fighting began for real a week later with the British opening an offensive that failed to make much headway. With two weeks to bring in troops and prepare their positions, the Axis had built a strong bridgehead around the colony’s capital and largest commercial port, Tunis, and the French naval base at Bizerte. Troops and supplies flowed across the Sicilian Channel by air and on the German and Italian landing craft that had been built for the abortive invasion of Malta planned for the previous year. The British skirmished with a German probe on the next day, but fighting began for real a week later with the British opening an offensive that failed to make much headway. With two weeks to bring in troops and prepare their positions, the Axis had built a strong bridgehead around the colony’s capital and largest commercial port, Tunis, and the French naval base at Bizerte. Troops and supplies flowed across the Sicilian Channel by air and on the German and Italian landing craft that had been built for the abortive invasion of Malta planned for the previous year.

British and American troops continued to arrive overland from Algeria, but the participation of French troops of the Armée d’Afrique proved crucial in the early days. French troops fought off two German attacks on the Medjez Bridge on 19 November, three days before the North African Agreement formally placed them on the Allied side.

An Allied offensive opened in late November, assisted by battalion-sized parachute and amphibious landings, but made little progress. All of the ground gained, and more, was lost to an Axis counter-offensive in early December spearheaded by the 10th Panzer Division. The Allied “race for Tunis” had failed.

Both sides brought in more reinforcements, and in late December the Allies tried again, only to meet bloody failure. The French had some success at the end of the month, but lacked the strength to exploit their gains. And now the focus of both sides shifted as Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Army Africa approached Tunisia’s southern border following a precipitous rout across the Italian colony of Libya.

In particular the Allies appear to have greatly over-estimated the combat potential of Rommel’s forces, which were mere shells of the proud formations they had once been and would need massive infusions of men and materiel to become effective again. But their battle-hardened cadres could form the core of good divisions once again, and the Axis sought to get them to Tunisia while the Allies wished to stop them.

That caused the front to shift southward in January 1943. Bad weather also limited operations, as both sides continued to bring new formations to Tunisia. By late January the British First Army had five divisions, the American II Corps had six, and the French XIX Corps had two undersized divisions.

When Rommel’s depleted divisions arrived, he urged an immediate attack to disrupt the Allies in Tunisia, before Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army caught up with the fleeing Axis units. At the end of January the newly-replenished 21st Panzer Division struck the French at Faïd Pass, driving them back and inflicting massive losses on American tanks when they tried to intervene.

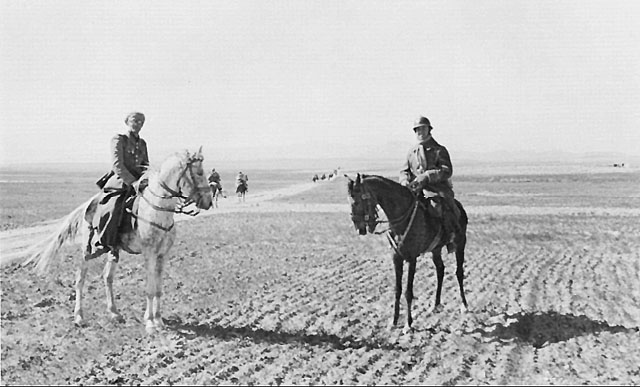

French Spahis near Sidi bou Zid, 14 February 1943.

Following up that success, the Germans added 10th Panzer Division and returned to the attack, destroying 103 American tanks and 280 other vehicles. Over 2,500 American soldiers turned up missing. The Americans promptly organized a counter-attack, which failed miserably.

Rommel added more forces – the composite Afrika Korps Assault Group and the Italian 131st “Centauro” Armored Division – and attacked the Allied positions in and around the vital Kasserine Pass leading to Algeria. The British held their ground, but the American front crumbled. A stout defense based on British infantry and American artillery finally stopped the advance, and Rommel called off the offensive.

By this point Montgomery’s divisions had arrived in southern Tunisia, and Rommel – now named commander of all Axis forces in Tunisia – turned to attack them. That effort failed amid heavy losses, and both sides now returned to building up their forces while the Allies sacked a number of their generals. Feeling the position in Tunisia doomed, Rommel flew to Europe to argue first with the high command and then with Adolf Hitler that the Axis should withdraw. Those discussions resulted in his quiet firing under the guise of sick leave.

Meanwhile the German Fifth Panzer Army holding the northern portion of the Axis front launched what would be the last Axis offensive in Tunisia, attacking the British V Corps in heavy rain. The operation went poorly from the start, with the British offering strong resistance and the German vehicles becoming mired in the springtime mud. When the offensive finally petered out the Axis had lost 5,000 men and 71 tanks, including nineteen of the new Tiger tanks.

By mid-March the Allies felt strong enough to resume the offensive, with Montgomery’s Eighth Army attacking the Mareth Line fortifications with the army-sized U.S. II Corps, now led by George S. Patton, assaulting the passes to the north-west of the Mareth Line and threatening its Axis defenders’ line of retreat. The British assault broke through the inadequate French-built Mareth fortifications while the Americans also finally found some success.

While Eighth Army and II Corps fought in the south, the British V Corps undertook a counter-attack of its own. With Moroccan goumier light infantry spearheading the way in the rough mountain terrain, the British recaptured all the ground lost in the Axis offensive and pressed on several miles further.

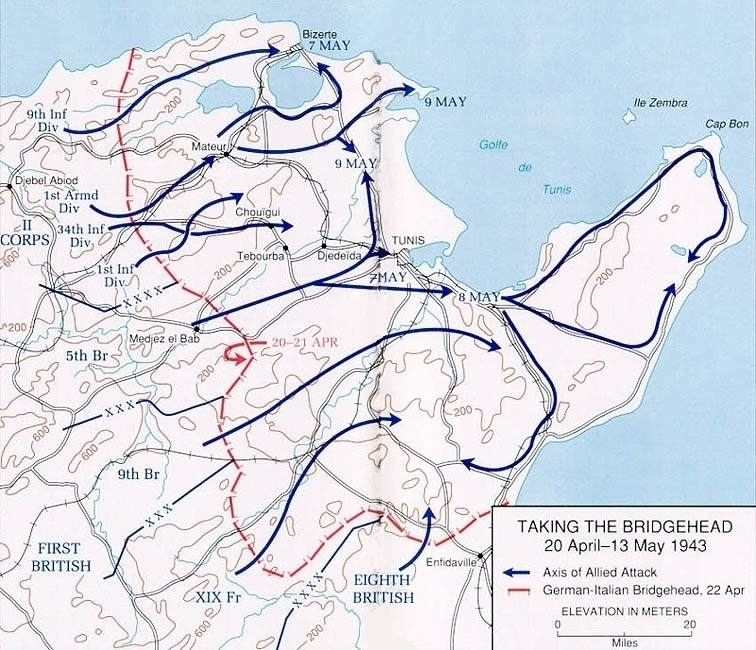

By early April, the Axis defenders were in deep trouble. Determined American and British logistic efforts had brought a steady flow of supplies to the front and built new, all-weather airfields in western Tunisia that gave the Allies air superiority over the entire colony. British warships operating out of Malta also intervened in the Sicilian Channel to interdict Axis sea traffic, though the Allied dominance in the air had already cut off that line of communications. The Axis could no longer supply or reinforce their armies in and around the ports of Tunis and Bizerte, nor could they rescue their trapped divisions.

The end in Tunisia.

Fighting continued through the remainder of April, but the Axis had no chance to escape nor could they hold their position. Despite hard fighting by many Axis units, their bridgehead steadily shrank until Tunis fell on 7 May and German formations began to surrender. Italian units held out for another week, with Giovanni Messe finally surrendering his Italian First Army (the former Panzer Army Africa) only after a direct order from Benito Mussolini.

Though sometimes portrayed as having delayed the Allied invasion of Sicily, the Axis attempt to defend Tunisia doesn’t seem to have accomplished even that much. Once the Allies inevitably completed their network of forward airfields, withdrawal became impossible. Failing to commit to Tunisia in the first place could have had negative repercussions for the Axis alliance, as Allied possession of bases in northern Tunisia would have opened Sicily to relentless air attacks. Withdrawing earlier would have meant writing off Rommel’s shattered army – by the time he made his tour advocating for a pullout, it was likely already too late.

Click right here to order Panzer Grenadier: An Army at Dawn right now.

You can order La Campagne de Tunisie right here.

Sign up for our newsletter right here. Your info will never be sold or transferred; we'll just use it to update you on new games and new offers.

Mike Bennighof is president of Avalanche Press and holds a doctorate in history from Emory University. A Fulbright Scholar and NASA Journalist in Space finalist, he has published a great many books, games and articles on historical subjects; people are saying that some of them are actually good.

He lives in Birmingham, Alabama with his wife, three children, and his Iron Dog, Leopold.

Want to keep Daily Content free of third-party ads? You can send us some love (and cash) through this link right here.

|